To anyone outside of engineering, releasing software sounds like a routine administrative task. You finish the work, you click a button, and the new features appear. In reality, it is more like performing open heart surgery while the patient is running a marathon. Even after decades in the industry, that “deploy” button still carries a specific kind of weight.

What is “Production” anyway?

For those not in the weeds of code, production is the “real world.” It is the version of the site where real money changes hands and real data is stored. Before code gets there, it lives in “Development” or “Staging” environments. These are essentially practice stages where we try to break things before the public sees them.

The move to production is the moment of truth. It is when the software stops being a project and starts being a service.

The Staging Illusion

We spend a lot of time and money trying to make staging look like production. It is our safety net, the place where we catch the configuration leftovers and the API keys we forgot in the mad rush to commit. But “works in staging” is often just as dangerous a phrase as “works on my machine.”

Staging is a vacuum. It lacks the noise and the sheer unpredictability of the live environment. No matter how perfect your staging setup is, there is always one network rule, one permission flag, or one forgotten environment variable that only reveals itself when you hit the live servers.

The Data Paradox

We have mostly solved how we manage database structures, but the data itself remains a ghost in the machine. In development, we test with databases full of years of junk. We think we are being thorough, but we often miss the “clean floor” problem. When you go to a fresh production environment, you have empty tables. Sometimes the application behaves completely differently because it simply does not know how to handle the void.

Then you have the opposite problem: drifted context. Old data in production often means something slightly different than what the current code expects. Those ten year old edge cases are things no developer could ever dream up in a sprint planning session.

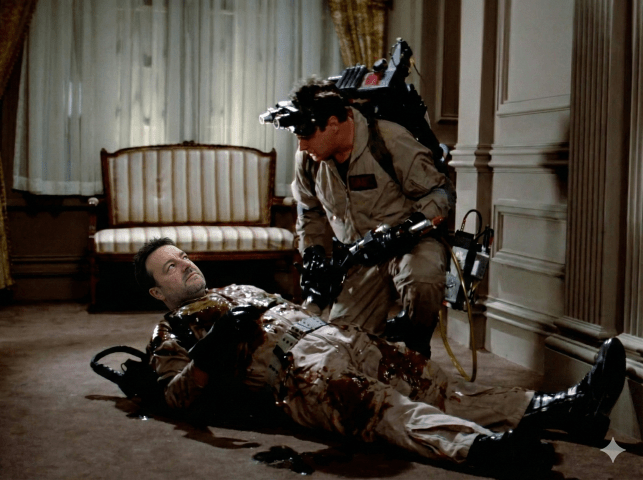

The Landing Gear Moment

When it comes to scale, I always think of an airplane coming in to land. The landing gear is lowered, and for a moment, the wheels are at 0 mph. The second they touch the tarmac, they have to spin up to 160 mph instantly.

Releasing a large scale site is exactly like that. You go from the quiet of staging to the friction of the real world in a heartbeat. Caches are cold. The load is hitting. Everything that worked perfectly in isolation now has to survive the heat of thousands of concurrent users. If those wheels do not spin up fast enough, things start to smoke.

The “Big Bang” Necessity

The industry preaches that we should “release small, release often.” It is a great methodology and it definitely minimizes risk. But let’s be honest: sometimes you are forced to go big. Whether it is a platform rebuild or a massive architectural shift, you occasionally need that “Big Bang” release just to ensure you have a clean, singular rollback path. That is where the anxiety peaks, because you are moving the whole mountain at once.

First Contact

Perhaps the biggest wildcard is the customer. Production is often the first time real people get to offer real feedback. Even in a staged beta, customers will use your software in ways you never foreseen. They click things you thought were unclickable. They are the ultimate stress test, revealing issues in areas you never thought to check.

The External Handcuffs

Then there is the stuff we do not even control. You can have the best code in the world, but you are still at the mercy of third party APIs and payment gateways. If a production API key is not configured for the right volume, or a specific account flag is missing on their end, you are dead in the water. It is the ultimate “gotcha” because you cannot fix it in your own code.

The Aftermath and the Friday Rule

A release is not over just because the progress bar hit 100%. The real work starts the moment the code is live. We keep a tight eye on the logs, looking for the first sign of an error that didn’t show up in testing. Communication is key here, making sure the team and the stakeholders have clear release notes so they know exactly what changed.

This is also why we generally do not release on a Friday. You want to release at a time when traffic is at its lowest, but when your full team and QA staff are still around to handle corrective action. You want plenty of runway left in the day. “Friday Afternoon Syndrome” is real, and the last thing you want is to be debugging a critical landing gear failure at 8 PM on a Friday night.

So, the next time you see a “New features are live” banner on your favorite site, just know there is likely a room full of engineers staring at logs and drinking way too much coffee. It is a high stakes game of moving parts and unpredictable variables, all being dictated by the Release Manager, who is responsible for the whole orchestration of pieces.

Bet you didn’t know releasing software was so exciting?

AI Disclaimer: Gemini Nano Banana Pro was used to generate the image.

![[Review] PostgreSQL Mistakes and How to Avoid Them](https://alan.is/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/mycousinvinny-small.png?w=643)