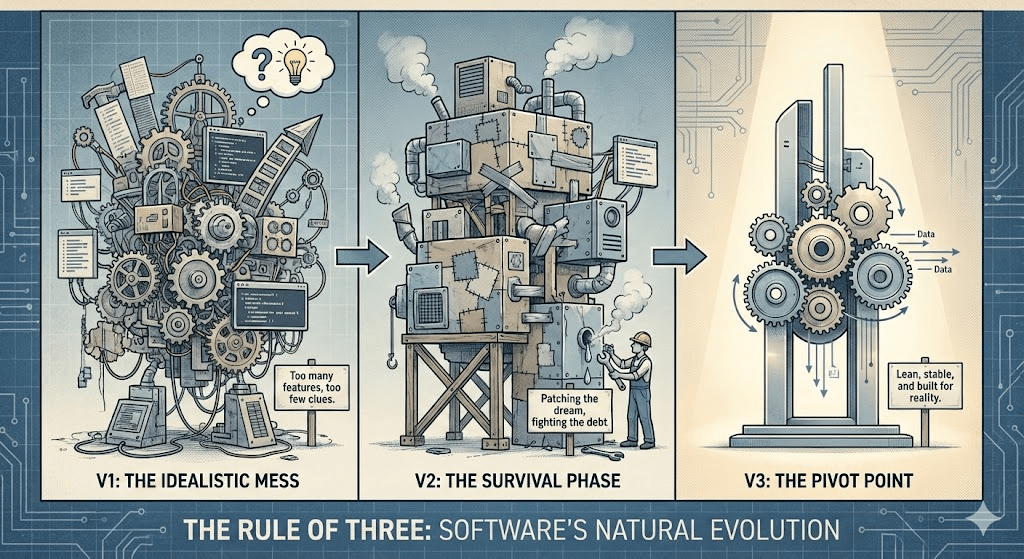

There is a recurring pattern in software engineering that rarely gets mentioned during the initial sprint to market. We spend our lives building systems, but we almost never get them right on the first or second attempt. It is usually version three where the magic happens. By that point, the ego has been bruised, the users have complained, and the reality of the problem has finally set in.

The Three Acts

- Version 1 is the idealistic mess. You are trying to prove a concept while simultaneously attempting to build the most perfect architecture known to man. You throw every pattern in the book at it. In reality, it is a bloated assembly of guesses. You are solving problems you think you might have, rather than the ones you actually do. It is a first date where you are trying far too hard to impress.

- Version 2 is the survival phase. You have launched and the feedback is pouring in. You realise half the features you spent months on are being ignored, while the one tiny utility you added as an afterthought is the only thing people care about. You spend this version patching, tweaking, and trying to force Version 1 to do what it should have done originally. It is a Frankenstein of the original vision and urgent fixes. It works, but it is heavy and the technical debt is starting to smell.

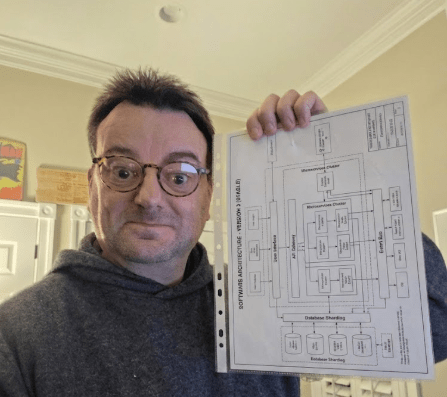

- Version 3 is the pivot point. This is the rewrite. You finally understand the problem. You look at the thousands of lines of code from the previous versions and realise most of it is noise. This is where you start deleting. You bin the over-engineered abstractions and the “just in case” logic. You build what you actually need. It is leaner, faster, and finally stable because it is based on evidence rather than speculation.

Lessons from the big boys

We have seen this across the industry for decades.

Windows 3.1 was the moment Microsoft actually figured out a usable graphical interface that didn’t feel like a toy or a constant crash waiting to happen. Before that, it was a curiosity; after that, it was an empire.

MySQL 3.23 was the version that truly put the database on the map. It introduced the MyISAM table handler and integrated enough stability and speed to become the backbone of the early web. It wasn’t perfect, but it was the first time it felt like a professional tool rather than a hobbyist project.

It isn’t just operating systems and databases. We see it in the frameworks and libraries we use every day.

React 16 (Fiber) was a complete rewrite of the core reconciliation engine. Version 0.x was the “is this even a good idea?” phase. Version 15 was the stable version everyone tried to make work for massive apps, but it hit a wall with synchronous rendering. Version 16 took everything the team learned about how browsers actually handle rendering and threw away the old engine. They simplified the mental model while making the internals infinitely more sophisticated.

Angular took a more aggressive path by performing its total rewrite at Version 2. It was a “scorched earth” approach that abandoned the original AngularJS (v1) entirely. But even then, the framework didn’t truly settle into its rhythm until it reached Version 4 (having famously skipped Version 3 to align its internal packages). It was only then that the tooling, the CLI, and the stability finally matched the ambition of the original rewrite.

Python 3 was the hard reset. Version 1 was the proof of concept. Version 2 was where it became the world’s favourite scripting language, but it was messy because handling strings and Unicode was a disaster. Version 3 broke things on purpose. It forced developers to stop taking shortcuts and removed the “magic” that made version 2 unpredictable.

Spring Framework followed a similar path. Version 1 was an XML nightmare. Version 2 tried to make that nightmare more manageable by adding even more features to the XML. Version 3 was the breakthrough. It introduced Java-based configuration and annotations. The architects realised the problem wasn’t how to manage XML better, but why they were using XML at all.

The Biological Inevitability of the V1

We often look at this cycle as a failure of planning, but it is actually a natural evolution. You cannot skip the first two phases. You cannot “architect” your way out of the learning curve. Even when we start something entirely new (the “Greenfield” dream) we walk into it convinced that this time, we have it. We tell ourselves that because we have ten or twenty years of experience, we will nail the v1.

We don’t.

We repeat the same process again. We over-engineer because we are excited, or we under-engineer because we are rushed. This isn’t a lack of skill; it is just how human beings solve complex problems. You have to touch the hot stove a few times before you understand the thermodynamics. Acceptance of this cycle is what separates a senior architect from a dreamer.

Finding the Dead Weight

Before you can build Version 3, you have to identify what to kill. In a Version 2 codebase, the dead weight is usually hiding in plain sight.

- The Just In Case Abstractions

Look for the generic wrappers and interfaces that only have one implementation. You wrote them because you thought you might swap out the database or the messaging queue. You won’t. If you haven’t swapped it in three years, delete the abstraction and use the concrete implementation. - The Ghost Features

Check your telemetry. There is almost certainly a section of your app that was a “must have” during a frantic meeting in 2023 but has seen zero traffic in six months. Code that nobody uses is just a hiding place for bugs. Stop maintaining it and bin it. - The Middleware Swamp

In Version 2, we often solve problems by adding layers. If your request pipeline looks like a game of Jenga, you have a problem. Version 3 is about collapsing those layers. If a piece of logic doesn’t add value to every single request, it shouldn’t be in the global middleware. - The Configuration Labyrinth

If your config file is three hundred lines long and half of those flags are “temporary” overrides from a deployment two years ago, you are in Version 2 hell. Hardcode the sensible defaults and remove the toggles that nobody remembers how to use.

The Architecture of Deletion

The common thread here is that by Version 3, the architects stopped adding and started subtracting.

In Version 1, you add a feature because you think you need it.

In Version 2, you add a feature because a customer asked for it.

In Version 3, you realise that both of those features were actually covering up a flaw in the core design, so you delete the features and fix the core.

Stability doesn’t come from a lack of bugs; it comes from a lack of moving parts. If you are currently building a system and it feels like you are fighting the code to make a simple change, you are likely stuck in Version 2.

The path to Version 3 is usually paved with the stuff you are brave enough to throw away.

Editorial disclosure: Gemini AI (voice mode), was utilized to help collect my thoughts while I drove, verify my industry examples (and found another I wasn’t aware of) and then to review the final piece once I wrote it. It also produced the summary text. Images were generated using Nana Banana Pro.